Stock-Based Compensation – is it Real or a Fugazi?

Yes . . . a blog post about Stock-Based Compensation (SBC). You might be wondering why I would willingly write about such a seemingly dry topic. While normally it’s a non-issue, it has been an increased area of focus over the last few years. There has been egregious amounts of stock-based compensation within the tech industry and some high-profile investors like Warren Buffet, Jim Chanos and Daniel Loeb have been calling out the excessive use of SBC and “adjusted earnings”.

On the other side of the debate, many technology companies continue to exclude the cost of SBC from earnings and there was a particularly entertaining clip of Keith Rabois (Opendoor co-founder), where he came out swinging in defence of ignoring SBC, calling it fake - a fugazi. (The SBC bit starts from 1:40 below).

Who is right? Is SBC real, or is it a fugazi? Dilution is real, so SBC has to be real. Case closed . . . right?

I believe the discussion is nuanced because in some instances the accounting cost of SBC can significantly overstate the real cost of SBC. However, I agree that SBC usage in the technology space has been excessive and the recent focus on efficiency will force companies to clean up their acts.

Before diving in, let’s just cover some basics.

What Is Stock-Based Compensation?

Stock-Based Compensation is when a company pays its employees in stock and/or options. The key premise underlying SBC is that it creates alignment between employees and shareholders as employees now have skin in the game and have more incentive to get the share price up, which is ultimately what shareholders want.

Stock-Based Compensation sounds like a good thing – what’s the issue?

Creating more alignment between stakeholders is a good thing . . . but too much of a good thing can be bad. The key issue is that there has been too much SBC in the technology sector. The other issue is that some management teams have seemingly been ignoring the cost of SBC over the last few years, presenting their financials in a way that excludes the cost of SBC.

To illustrate the point, check out the financials of Salesforce and Atlassian. In FY23 Salesforce made over $31b in revenue and only $1b in net operating income - a tiny 3% margin. Atlassian generated over $2b in revenue in FY22 while losing over $100m. However, after adding back SBC and other adjustments, Salesforce and Atlassian claimed to have generated profits of $7.1b and $600m.

The cynics view this as gaming the system as management have found a way to dish out as much of their expenses below the line via generous SBC packages, while seemingly hitting their “earnings” targets. As the market accepted adjusted profits as a benchmark, this created an incentive for management to shift as much of their cost base into SBC – which is exactly what has been happening. To be fair, this also happens in many non-tech industries with EBITDA being the main culprit.

But . . . is all of that SBC cost real? Not All SBC is created equal. There are two main types of SBC – Stock Options and Stock Grants.

Options: the best SBC

Options are great tools that create alignment between shareholders and management. Most option plans are issued with a strike price equal to the current market price. As a shareholder, if an option is issued with an exercise equal to the current market price, is there really that much dilution? Let’s use a hypothetical example below.

In this scenario, the stock is worth $1 and employees are granted 5 options with a $1 strike. While the share count or EPS has been diluted, the enterprise value of the company is unchanged. As a shareholder I have already factored the impact of the options within diluted market cap (plus some restricted cash). However, within the accounting statement, these options would represent a significant cost as the option is valued using the Black-Scholes model, which is influenced by factors such as duration or the volatility of the underlying security. Using Black-Scholes these call options would be worth $0.41 each or $2.05 in total. So, within the P&L this company would be recording a $2.05 expense equal to 41% of their total profits.

As an investor in the above business, did that option grant really cost me that much? Did it really result in a 41% reduction in the free cash flow of my business? From my perspective it didn’t – especially considering I have already modelled for the dilution.

In a case like this, I believe the accounting cost of SBC is mostly a fugazi. While I agree that the options issued above have value, I just do not think it represents a significant cost to me as an equity holder – especially not to the extent that the accounting P&L would imply.

Stock grants: this is not a fugazi

Stock grants are when employees are given shares that vest based on tenure and are generally not linked to a KPI. It is a stretch to treat this as a “non-real” expense. Ignoring this cost while continuing to give away stock is the equivalent of Modern Monetary Theory for companies.

Salesforce is regularly called out as one of the bad actors when it comes to SBC, especially given their size and maturity. Management are also prolific sellers of the stock.

Across FY22 and FY23 Salesforce granted 38m in shares to its employees, which accounted for $4.4b and $3.8b in value and 17%/12% of Salesforce’s revenue. Unlike options, the stock price does not have to go up for employees to receive these grants and employees do not have to contribute any capital to the business. Salesforce (and many others) continue to exclude the cost of these issuances from their earnings, which just acts as a hidden tax on shareholders (just like inflation or money printing).

Final Thoughts

Options > Grants

Shareholder friendly option plans are a great way to create alignment between management and shareholders.

The accounting cost of options can significantly overstate the real world cost of the options issued, and I contend that the accounting cost can be a fugazi. On the flip side, the accounting cost of options creates a nice cash tax shield.

Stock grants are a straight up costs and I struggle to see how we can exclude this from operating income.

As always, investors need to assess investments and SBC plans on a case-by-case basis.

FCF > Earnings: Focus on Free Cash Flow per Share

I understand why the cynics are sceptical when they see a huge cost item in the P&L that management try to ignore. However, as the most conservative of investors will tell you, ultimately the focus has to be on cash.

Irrespective of how management teams decide to allocate capital (i.e., opex vs capex vs dilution), the ultimate metric that underpins a business’s value is Free Cash Flow per Share.

“Why not focus first and foremost, as many do, on earnings, earnings per share or earnings growth? The simple answer is that earnings don’t directly translate into cash flows, and shares are worth only the present value of their future cash flows, not the present value of their future earnings. Future earnings are a component—but not the only important component—of future cash flow per share.” Jeff Bezos - Amazon’s 2004 shareholder letter

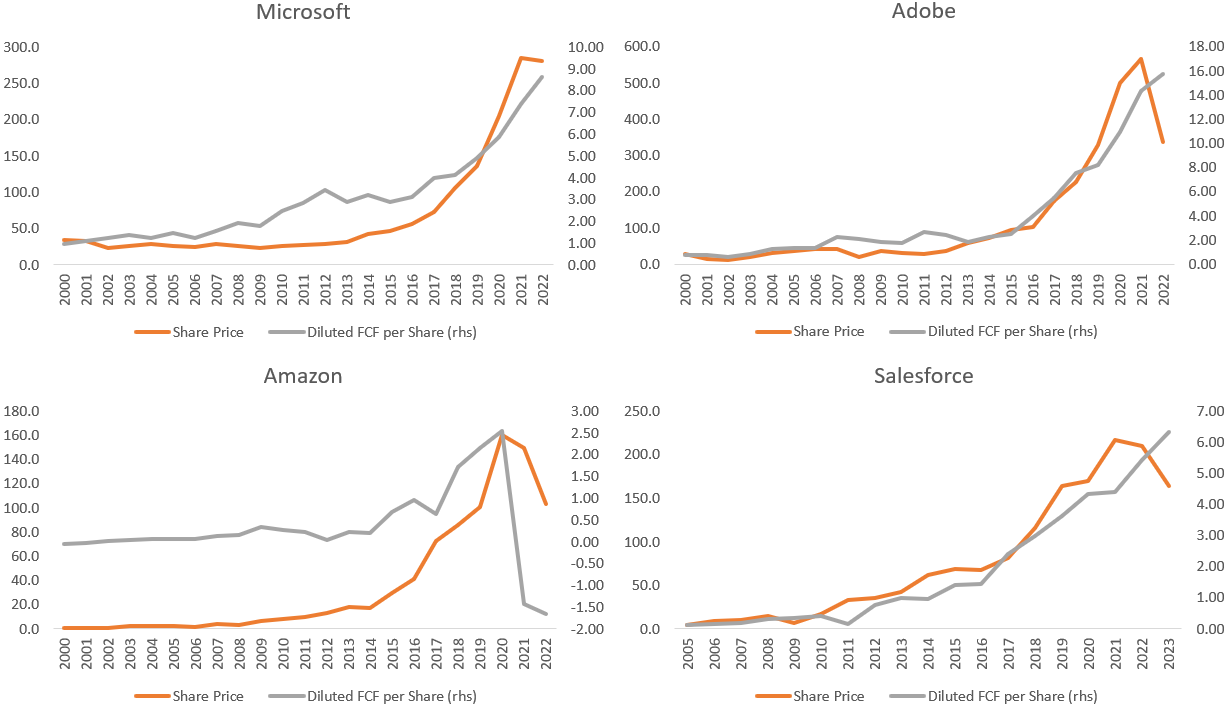

As the charts show, despite plenty of dilution across the stocks below, they have increased Free Cash Flow per Share - which has generally created value. (Note: Share Prices & FCF are as of financial period end)

Tech Dilution has been excessive but should come down

I agree with the overarching view that SBC/dilution within tech has been excessive. This is mainly due to the fat that has built up within the tech sector over the last few years.

Investors have always assumed SBC falls as companies mature, however this hasn’t been the case as even mature tech dilution has doubled over the last few years. Does Salesforce - with its $200b market cap - really need to dilute their share-base by ~5% every year to achieve their business objectives? Probably not.

Given the recent focus on efficiency, I expect SBC issuance to tighten up.